To the Moon and Back

When she was 7 or 8 years old, Rebekah Davis Reed ’93 learned that her birthday, July 18, is also the birthday of John Glenn, the first U.S. astronaut to orbit Earth.

“He was born exactly 50 years before I was, and I think learning that at a young age caused me to ask a lot of questions about what he did and why it was important, and why NASA was important,” she says.

Today, Reed is associate director of exploration, integration, and science at NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. She and her team are helping the Artemis program to return the United States to the Moon in the next few years. Artemis will send both the first woman and the first person of color to the moon, and ultimately Reed’s team is planning for exploration on Mars, too.

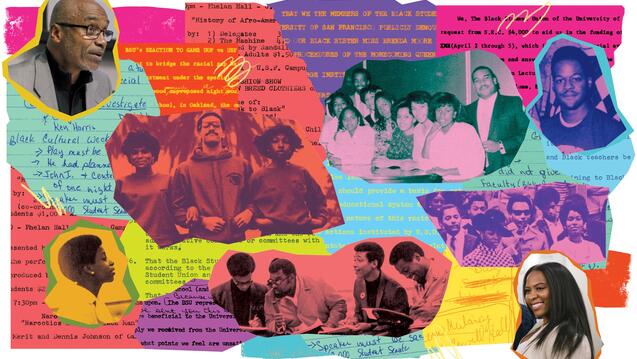

From Fine Arts to Food Security

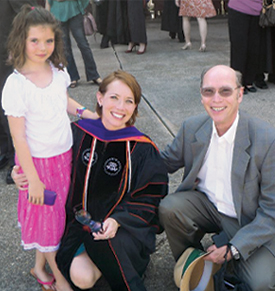

Although she was interested in space from an early age, Reed didn’t chart a course straight to NASA. She started off in the fine arts program at USF — her father, Richard Davis, was chair of the communications department — but soon realized that art wasn’t her strong point. “But I was really good at history,” she says. “I had some really amazing teachers who taught me how rich history can be, and they encouraged me to do a lot of original research.”

After USF, Reed earned a PhD in history at Georgetown University, studying diplomatic history and Middle East history. She went into public service, joining the USDA’s foreign agricultural service, where she helped create the United States’ first roadmap for global food security and worked on U.S. delegations to the United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development, developing international food security initiatives.

“My career has absolutely not been a straight line, and it’s something that I talk with interns at NASA about all the time,” she says. “Those detours can be the very best parts of your life and your career. It’s really important to have a plan, but you have to be open to opportunities that don’t lie directly on that straight path.”

Next Step: NASA

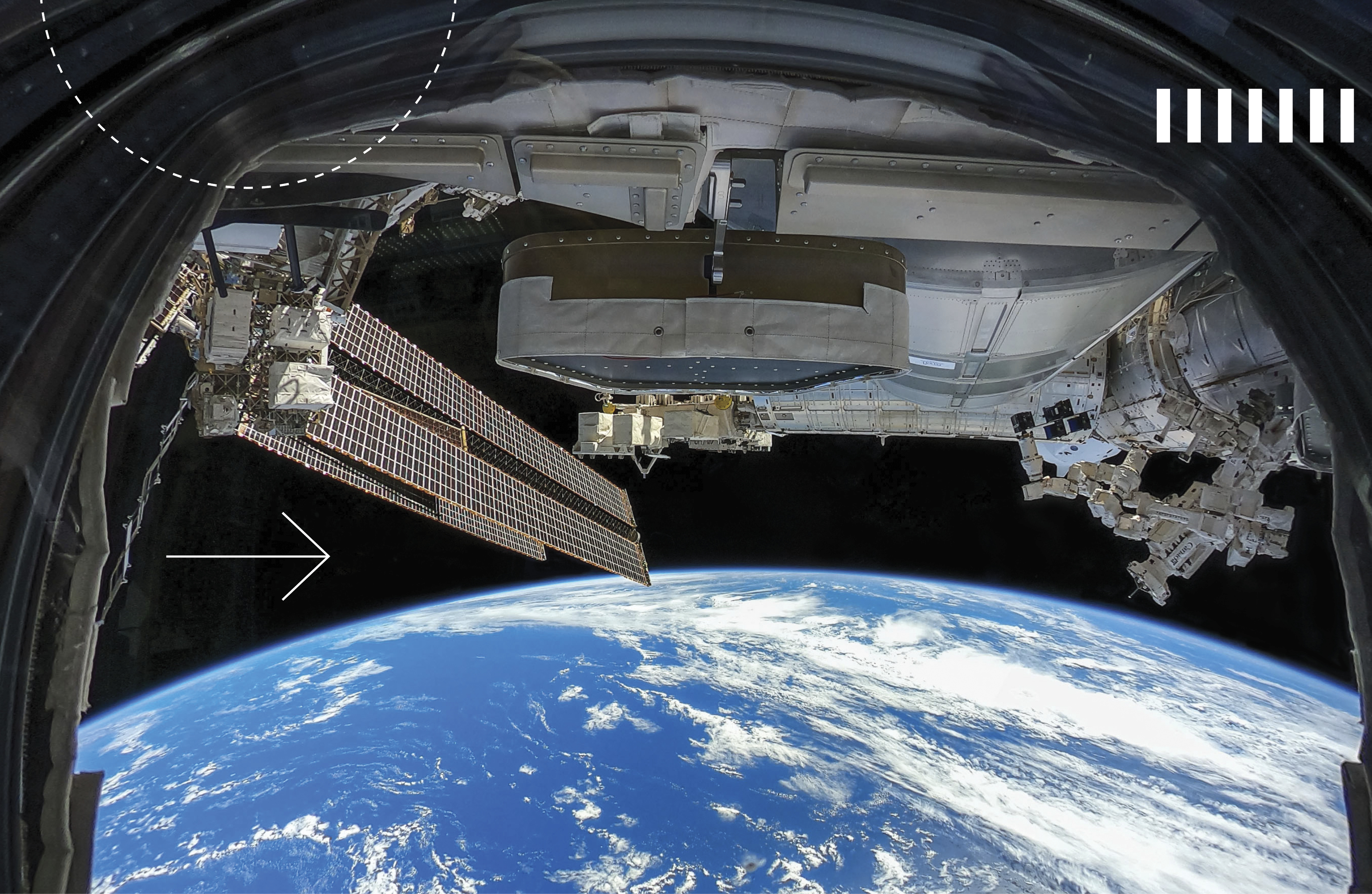

In 2000, NASA hired Reed as an international relations officer supporting human space flight programs. At the time, the agency was preparing the International Space Station (ISS) to receive its first crew, and Reed traveled the world, visiting space station partners and renegotiating ISS agreements.

Three years later, she moved to Houston to work at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. She also went back to school to earn JD and LLM degrees at the University of Houston Law Center. Her LLM research was focused on bioethics, particularly the ethics of medical care in extreme environments like space. She rose at NASA to chief of the space and occupational medicine branch and later to program manager for crew health and safety.

My career has absolutely not been a straight line, and it’s something that I talk with interns at NASA about all the time,” she says. “Those detours can be the very best parts of your life and your career. It’s really important to have a plan, but you have to be open to opportunities that don’t lie directly on that straight path.

Today Reed oversees about 15 members of the exploration, integration, and science leadership team, with more than 180 NASA employees and more than 300 agency contractors working on her team. They tackle questions such as where to land on the moon? How to manage the various vehicles there? How to collect astro materials, such as geological samples of the moon and Mars? How best to study those materials to answer questions about the origin and evolution of our solar system and of life?

“I get to lead leaders, which I think is the best job in the world,” she says. “Most of my time is spent talking to my team, identifying issues, and supporting them so that they can do the critical work of getting us to the moon and eventually to Mars.”

The Art of Leadership

Reed likes to talk about how her liberal arts education prepared her to be a leader.

"I think leaders have to be good at a lot of different things. You have to be good at communications, problem-solving, critical thinking, maybe most importantly, asking great questions and understanding the big picture. And those are things that a liberal arts education absolutely prepares you for,” she says.

Brandon Brown, author of The Apollo Chronicles and a professor in USF’s physics and astronomy department, said Reed models the type of NASA leader he is familiar with.

“Rebekah’s story resonates deeply with NASA’s early DNA,” Brown says. “People took all sorts of different paths to arrive at this ambitious work. While we often picture rooms full of aerospace engineers, the space program has always relied on every sort of expertise humans can offer, from new types of welding to innovative sewing — not just rocketry. Most of all, I love hearing that she owns and appreciates the difficulty of their work, trying to convey people safely into space and back.”

One of the most meaningful parts of the Artemis program to Reed is the commitment to put women and people of color on the launches to the moon and beyond.

“It’s important to me and important to NASA that every child, every person in America, can see themselves in our mission,” she says. “Our goal isn’t just to send humans back to the moon and onto Mars, but to inspire the next generation of explorers and scientists who will enable the next great leaps in humanity that take us into the stars. I think we do that the best when people can picture themselves as a part of that mission.”

Mission: Mars

Reed says she gets goosebumps just thinking about witnessing a launch from Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Control Center.

“It’s very easy to forget how challenging space flight is, because we’ve gotten pretty good at it,” she said. “But when you’re sitting that close to the launch platform, and you can hear the sound of the engines starting up, and you can feel the vibration of the space shuttle pushing away from the earth, it gives you a really visceral understanding of how extraordinary it is that we can send humans off the face of the earth and then bring them back safely.”

Space exploration in the 2020s is busy. SpaceX, Virgin Galactic, and Blue Origin all sent their first crewed missions into space last year. There has been some backlash to these billionaire-funded efforts. Where does NASA stand with these companies?

“Partnering with American companies benefits NASA and industry,” Reed said. One of the agency’s goals in going back to the moon and on to Mars is to create a viable lunar economy, she said. And that means ensuring that commercial space companies can build the U.S.’s capacity to operate in space.

“When I joined NASA a little more than 20 years ago, we were creating the first permanent human presence in space aboard the ISS,” she said. “Today, we’re preparing to send women and men back to the moon — not just for a visit for a couple of days, but to stay and to actually learn how to live and work on another world.”

Beyond the moon is Mars. The goal? To build a sustainable outpost on another planet. “When we do that, we will become a multi-planet species, which is kind of amazing,” Reed says.

NASA, as it embarks on these big quests, needs people like Reed, says Aparna Venkatesan, a professor of physics and astronomy at USF.

“Space exploration touches on an increasingly complex web of fields including space law, planetary biocontamination and bioethics, how heritage sites are determined, the history of colonization of ‘frontiers,’ and the ethics of space mining,” Venkatesan says. “Rebekah’s experience and training in many disciplines will be critical in developing responsible, inclusive models of space exploration.”

For Reed, it all goes back to doing what you love. If she could give advice to herself as a USF student, or to today’s students, that’s what she would say.

"The key to having a meaningful and satisfying career is to figure out what you love and to find work that has meaning to you,” she says. “The most important thing of all is that you make a difference. And it’s important to make a difference at work, in your life, and in your community. If you can do that, I think you can consider yourself successful."

Photos by NASA