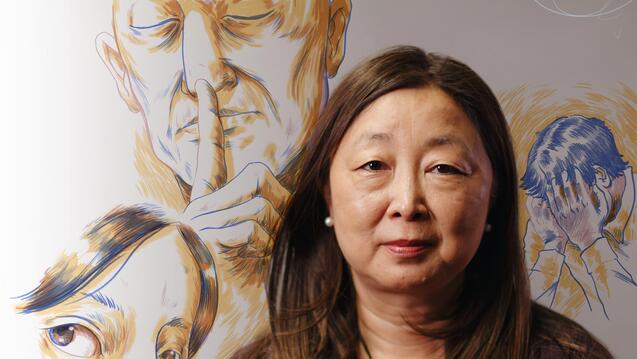

Meet Chinyere Oparah

USF’s new provost and vice president of academic affairs comes to the Hilltop from Mills College in Oakland, where she was a professor of ethnic studies before she served as provost and dean of the faculty from 2017 to 2021.

Job interview question! Tell us your background.

Well, I was born in Scotland, in Edinburgh. My mother was not supposed to be pregnant with a Black child, so I was almost immediately put into the foster system and eventually I was adopted. My adoptive family moved to the south of England and I was raised in a town called Winchester. Winchester is very symbolic and historic and unfortunately a magnet for far-right racist organizing at that time. We had school trips to the table that was the round table of King Arthur, right? It turned out to be a medieval replica so it was only 900 years old instead of what it should have been, but that was the context that I was raised in. It was not a context in which you saw a lot of Black people. When I was in my 20s I searched for and found my father, and I connected with my extended Nigerian family and visited our family’s compound and saw myself reflected in my great aunts. I also began to think of myself not as an outsider but as a global citizen, able to make a home wherever I find myself. But I’m getting ahead of myself. In Winchester, while I was in a public school, I took the entrance examination for the University of Cambridge and I got in.

What did you think of Cambridge?

I loved the intellectual challenge. But it was difficult in some ways. There were very few people like me there — there was a lot of classism, layered with racism. When I first got there I had to go to the dentist: painful tooth. And one of the students said to me, ‘Well, it must be very difficult for you to go to the dentist’ and I said why? She said, ‘Well, don’t you have to go to a special dentist?’ I said what do you mean? And she said, ‘Well, you know, because Black people have larger jaws so don’t they have a different dentist?’ She was buying into this ancient biological racism idea of craniology, and yet this was one of the country’s most elite universities.

Yikes. And from Cambridge you started your career in academia?

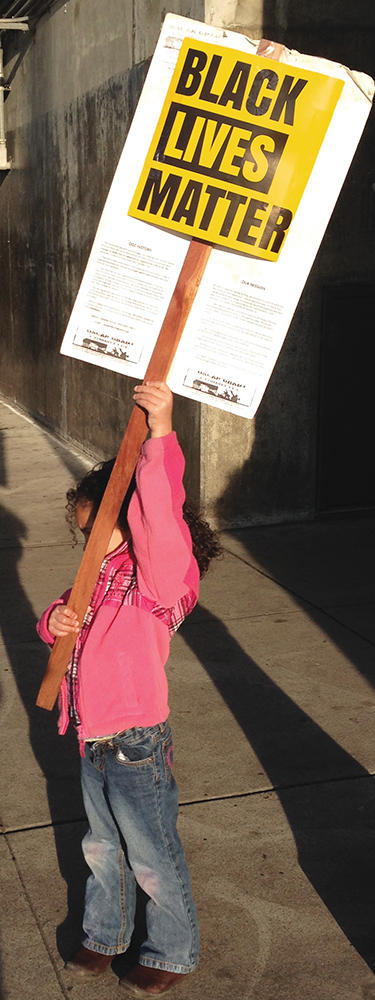

Not right away. I’ve had two careers. At Cambridge I studied modern and medieval languages, and my Spanish professor said to me, “Do you want to stay on and do some work with me around medieval Spanish?” and I said, “No! I’m going to go out and change the world!” So my first job out of college was as a community development officer working for the Cambridge City Council. During my last two years at college I had got involved in the Cambridge Black Women’s Group that was doing a lot of work around educational access and equity and anti-racism and supporting immigrant women as well as African Caribbean women. I just loved that work. And then after some years I ended up becoming the executive director of a national development agency for the Black nonprofit sector. That whole experience of grassroots community organizing and really listening to people and that real deep belief that the people, collectively, have the answers for their problems, and that when we come together, we can solve them — that has really been something that I’ve brought into my work as an administrator.

We can learn collectively from the racial reckoning and the political upheaval that we’ve had in the last year."

What attracted you to USF?

The students and how thoughtful and engaged they are. The faculty and how talented and passionate they are. The leaders and how mission-driven they are. The city with all its diversity and richness. The diversity here on campus. The sense of community here, and the Jesuit values in general and the social justice mission in particular.

What does a provost do, anyway?

The provost supports the community to offer a transformative education for our students — you know that really it’s all about the students, right? I see the job of provost as a science and an art. The science part is in the job description: I oversee all the academic affairs at USF. All the colleges and schools, all the academic programs, plus the library, plus admissions and financial aid. The academic affairs budget is about $320 million, so that gives you a sense of scope. I work with other leaders on campus to support the president’s vision, to implement the university’s strategic plan, and to help set our direction. And then there’s the art part. To me the art part is about cultivating a culture of trust and collaboration and shared governance, creating the conditions for innovation and creativity. So I as the provost am not doing all the innovation and designing and creating; I’m curating the conditions in which the work can happen. Now, the provost is not in the classroom, so I meet with students and also meet with faculty, with deans, with librarians to stay engaged and to stay as close to the classroom as I can.

What are your plans for USF?

I don’t really have plans. Plans imply that I know what’s best and that I’m going to lay down the law, like an edict. Instead, I have hopes. I hope that we can heal collectively from the suffering and the trauma and the isolation from the pandemic, and that we can learn collectively from the racial reckoning and the political upheaval that we’ve had in the last year. I hope that we can make our programs and our classes even more relevant and even more hands-on than they are now, with the teamwork and collaboration and the cross-disciplinary projects that employers want and that the world needs. I hope we can reach more students who would benefit from a USF education. I hope we can see the pandemic as a portal into new ways of doing things — curricula, programs, classes. Now, to pursue these hopes I’m going to meet with different people at USF and I’m going to listen. I’m a qualitative researcher. I like listening to people’s stories and hearing their perspectives. That’s how I formulate ideas about what we need to be doing. We can do far more together than one administrator could ever do.

So when you’re not working as a provost how do you spend your time?

For the last decade I’ve been involved in producing a series of articles and books in collaboration with a community organization based in Oakland called Black Women Birthing Justice, so that’s what I do on the weekends, the research and writing. Also, I’m a wife and a mother to an 11-year-old daughter. And we have a 3-year-old labradoodle — a mini labradoodle. Funny story about our dog: For years our daughter asked for a dog, prayed for a dog, brought home from the library every book on every breed of dog. She kept saying, “Can we get a puppy?” and I’d say no, because my wife and I don’t have time to take care of a dog. But one day my daughter said to me, “If you could just tell me why we can’t have a dog, then I’ll understand and I can accept it.” Now, when an 8-year-old says that to you, you realize you’ve been working too much and you realize there is no good reason you can’t have a dog. So we got a dog. We named her Chizara. That’s a Nigerian name that means “Spirit, the divine feminine, has answered my prayer,” and we named her that because Chizara is an answered prayer for our family. We take breaks now. We go for walks. I get my 3,000 steps a day. Cura personalis, right? I think self-care is a radical act. We all need to do more of it.

I think self-care is a radical act."