Designed By Disease

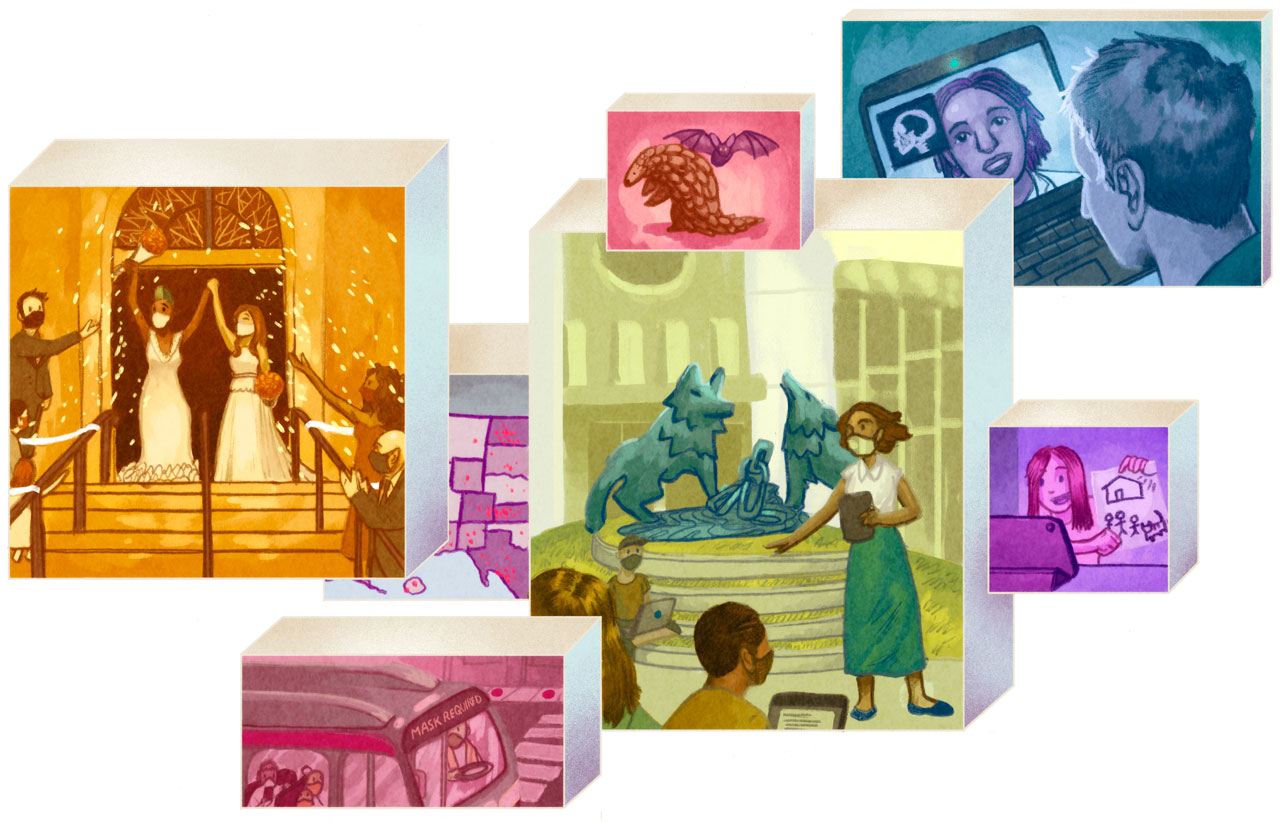

Many of us hoped, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, that we’d round the corner in a few weeks. A few months at most. Lockdowns and social distancing would work. The virus would be beat. We’d soon be back to normal.

We were wrong. We’ve now learned to live in a new sort of normal — while also retaining hope that we’ll round the corner. But even when we do round that corner, the pandemic has left its mark on our society. Will it continue to change our lives?

Scientists of the World Unite

First things first. Is it even possible to go back to a world free from suspicious glances, health anxieties, the six-foot rule?

Two things would have to happen first, says scientist Sarah Ives PSM ’15. For one, we’ll need a vaccine that could be distributed globally.

“Once we have herd immunity we can essentially treat this virus like any other virus that we can eradicate or nearly eradicate,” she says. “That’s the best-case scenario. There’s a lot that needs to happen before then.”

But some folks, like the elderly or people who are immunocompromised, can’t be vaccinated. So, second, we’ll need a treatment for people who are already sick, to keep those people from overwhelming the hospital system.

That treatment is what Ives’ company, Distributed Bio, is working on now — essentially a cure for COVID-19. Using adapted antibodies from the 2002 SARS virus, they’ve created an antibody treatment that’s proven in tests to save hamsters from the virus. The next step is to perform clinical trials.

Because of the pandemic, scientists are working at lightning speed. Whereas developing a vaccine can often take 10 to 15 years, experts are working to create one in one to two years.

“There are new ways now that we can share data with other scientists, internationally and rapidly,” says Ives, director of contact research at Distributed Bio. “I think that’s one of the silver linings of the pandemic: That we had to rethink the way we distribute science. I hope that means papers, scientific literature, and other information will become more accessible. Anyone should be able to see this information.”

In the meantime, how will our culture change over the next decade?

“The days of crowded, sweaty nightclubs may be gone, as well as large concerts, large work conferences at convention centers, large weddings,” Ives says. “Virtual school, work, and socializing may continue to play significant roles in our lives.”

But we will adapt and thrive, because that is our nature, Ives says. “I’m cautiously optimistic that within the next six months or less, both a vaccine and a therapy will be ready and we can begin to write the post-pandemic chapter of our history.”

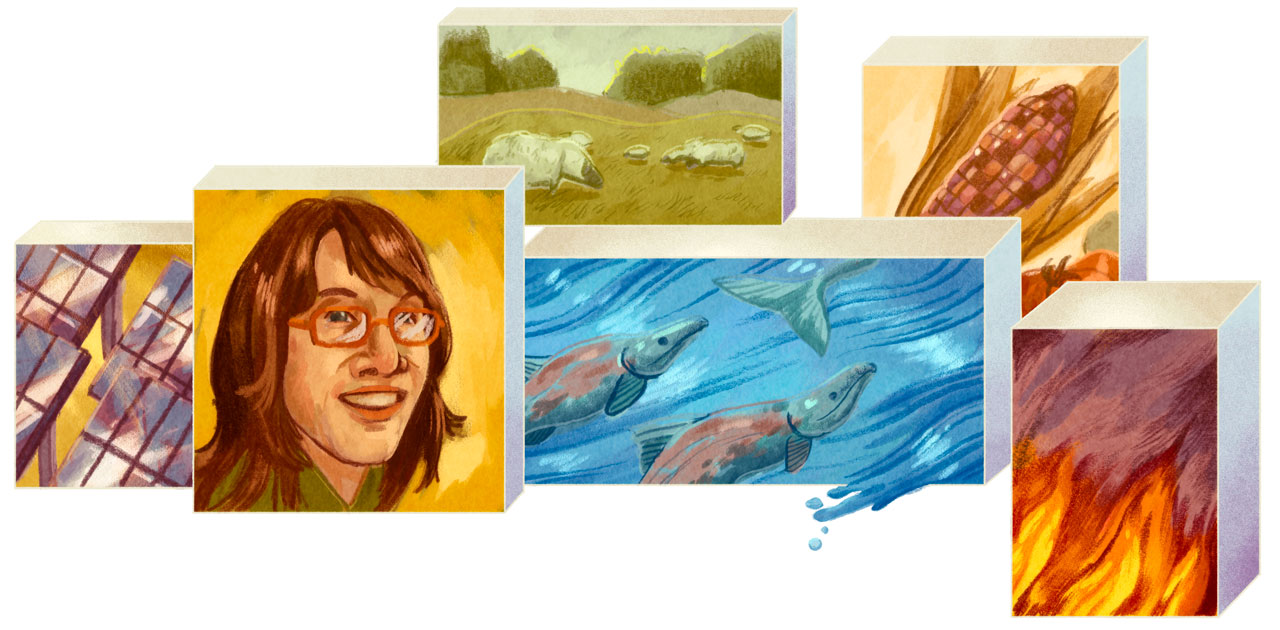

IN THE YEAR 2030

EARTH IS BETTER BUT STILL ENDANGERED

By Stephanie A. Siehr

In 2030, heatwaves and wildfires are still intense, but we know they will eventually ease thanks to global efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions in half during the 2020s. Expanded forests, whose restoration is led by indigenous stewards through the Land Back movement, are pulling carbon out of the air and providing much-needed cooling and habitat. From Amazonian jaguars and Pacific coho salmon to African elephants and mountain gorillas, the restored forests are pulling creatures back from the brink of extinction.

Storms and droughts are still threatening, but farmers and community collectives are feeding the world with diverse and resilient heirloom crops. The global shift to organic and regenerative agriculture — funded by the profits of disbanded agribusiness and pesticide companies — is restoring life and carbon to the soil. Food forests and pastures cover the landscape, replacing failing genetically engineered soy and corn monocrops.

The air is clearer with the rapid phase-out of fossil fuels. Jobs in energy conservation, renewable energy, and green affordable housing are in high demand. The World Trade Organization has a new mandate: support local production and equitable distribution of essential goods. Passenger travel and freight are greatly diminished. People are growing their local cultures rather than flying around to consume the cultures of others.

In 2030, the regeneration of communities will create new health and new balance in Earth’s climate.

Siehr is a professor of environmental science at USF.

WATCH SIEHR'S 2020 EARTH DAY MESSAGE

Pandemics are the New Normal

Even if we are able to contain COVID-19, we won’t be in the clear in the future, warns USF epidemiologist Marie-Claude Couture.

“We are always at risk of a new pandemic,” she says. Most new viruses, from COVID-19 to HIV/AIDS to Ebola, come from contact between animals and humans. As the human population grows and continues to encroach upon the animal world, there’s more and more chance of new viruses being spread from animal to human. This is called “spillover.”

“We need to invest in public health monitoring and in programs and research to prevent future pandemics,” Couture says.

Unfortunately, the United States’ response to the one we’re in now hasn’t inspired confidence, she says. For one, there hasn’t been a unified response between federal, state, and local governments. Whereas San Francisco has done a relatively good job of controlling the virus, other areas — including within California — have had more difficulty.

“We have several pandemic plans created by the government and the CDC that we have not followed well,” Couture says.

Part of the reason San Francisco has fared relatively well is because it was the epicenter of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. It’s had time to learn from experiences in public health. Couture hopes that in the future, when it’s time to face the next pandemic, the nation will also have learned.

“I hope we will learn from this mismanagement and our mistakes, but it depends on what the government wants to invest money in,” she says. “Humans have a short memory. And sometimes we forget and go back to our old behaviors.”

IN THE YEAR 2030

THE KICK IS UP . . . AND SHE JUST WON THE SUPER BOWL

By Will Exline MA ’12

- The NFL has three female kickers, and two teams in London.

- Major League Baseball has four players with $750 million contracts, and Mike Trout owns every all-time offensive record.

- The WNBA is a global powerhouse and the first choice for top international players.

- Major League Soccer has implemented the first promotion/relegation system in U.S. sports.

- The National Hockey League has a fifth division composed of six teams in Europe.

- Every NBA game is viewable for free on every device.

- Esports championships draw more fans than the Super Bowl.

Exline manages sports league and team partnerships at Twitter.

Masks Every Winter

When the pandemic started, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and some public health experts did not recommend that people wear masks in public. As more information became available, that advice changed. And that’s due in part to the work of USF data scientist Jeremy Howard.

In March, he decided to use mask-wearing as a case study to show his USF students how to combine and analyze data. He was surprised by what he found: the evidence that masks improved safety was strong.

That said, workers like nurses initially were told not to wear masks because it would scare patients. “It was very upsetting to see hospitals, which are meant to be the center of health, actively recommending against such a potent protective tool,” Howard says.

He started a group called #Masks4All, advocating the requirement of masks in public areas. If 80 percent of people wear a mask in public, he says, transmission of the COVID-19 virus could be dramatically slowed or even halted. He’s amplified his message through the Washington Post, CNN, and other national outlets.

In the future, Howard says, it will be more common to see people in Western countries wearing masks, even during the regular cold and flu season. It’s already common practice in East Asia, which has had a history of respiratory epidemics.

“Maybe this is something that we’re all going to keep doing, at least for a few more decades,” he says. “There might be an increasing shift toward people recognizing mask-wearing as a respectful thing, rather than people thinking, ‘That’s a strange behavior,’ or ‘Why are they bothering?’”

IN THE YEAR 2030

ALL LEARNING, NO GRADES

By Shabnam Koirala-Azad

WHAT IS YOUR VISION OF A 2030 CLASSROOM?

The classroom of 2030, all across the country, resembles the USF classroom of today. It’s a microcosm of community-building and learning, preparing students to use their intellect and inner spirit for the common good.

HOW WILL SCHOOLING LOOK DIFFERENT IN 2030?

Some of today’s educational policies, such as measuring achievement with test scores, have removed joy and creativity from education. In 2030, we’ve replaced test scores with holistic evaluations of each student, so we see each student as a whole being — mind, body, and spirit — instead of as a number.

WHAT DO YOU SEE AS THE BIGGEST SHIFTS FOR BOTH TEACHERS AND STUDENTS?

Technology can either enhance learning or create more barriers. The classrooms of the future will make students feel as if they belong and can take charge of their own learning. Instead of feeling confined within four walls or within a rigid curriculum, students will feel fulfilled in flexible spaces that consider their full humanity in the process of learning.

HOW CAN TEACHERS CREATE THE CLASSROOM OF 2030, TODAY?

Affirm the lived experiences and unique identity of each student. Recognize that teaching and learning have to do with the transformation of the self in order to transform the collective.

Koirala-Azad is dean of the School of Education.

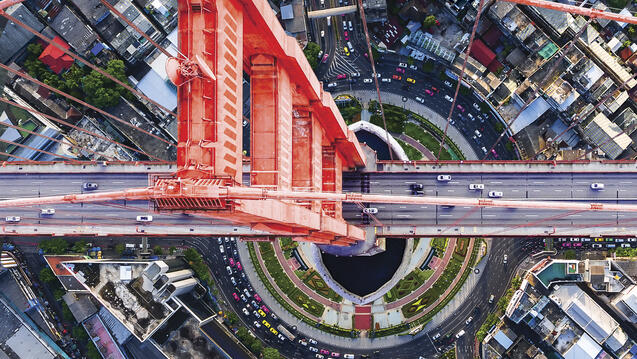

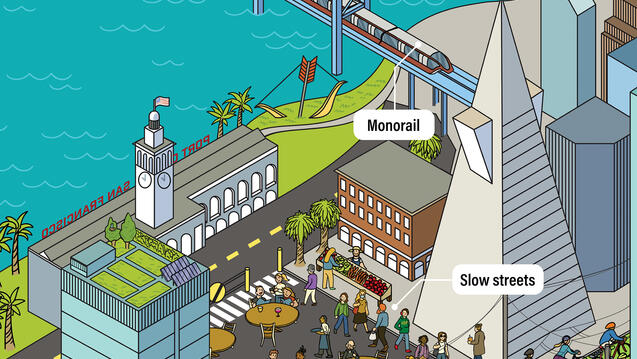

The City Shifts

It’s not only a pandemic we’re facing, but a potential economic shift as well. There was already a pandemic-caused recession, which the Congressional Budget Office predicted would end in the second quarter of this year.

In the short term, says USF economist Mario Muzzi, the key to normalcy is getting accurate rapid-result COVID-19 testing, a vaccine, and treatment. Those could be game-changers in terms of allowing people to be more comfortable returning to public space and events, taking public transportation, and even going to the dentist.

But if that doesn’t happen soon, the pandemic could fundamentally change the way the economy operates. A paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research shows that more than half of the Bay Area’s workforce can work from home. If people stay at home and can’t enjoy the vitality of an urban environment, what might happen? For one, people may decide they don’t need to be living in an expensive city.

And if offices do reopen, they may need to be redesigned with social distancing measures in place. Maybe employees will work from home some days and come into the office on others, in rotating shifts. Maybe offices will expand, so that there’s more interior space. Maybe even as people work from home, there will be more demand for office buildings.

“People are not going to forget about this quickly,” he says. “When people go back to the office or back to retail, I think the whole idea of standing apart from somebody in line, I think that’s going to stay.”

Meanwhile, the service industries, where people can’t work remotely, would also change, he says. Perhaps we’ll be ordering food from a machine rather than a server, or have packages delivered by drone instead of by postal workers.

Muzzi also notes the potential political ramifications of an extended crisis.

“You get people on the left and the right with easy solutions to complex issues,” Muzzi says. “Demagogues live in that type of environment. I’m afraid like anybody else that this might lead to some really bad results.”

A Change is Going to Come?

The pandemic has been especially bad for Black Americans, who are dying of COVID-19 at higher rates.

Sadly, says USF politics professor James Taylor, this is no surprise.

“The pandemic exposes the preexisting condition of being Black in America,” Taylor says. “Just look at the life expectancy of Black men in America compared to every other group. This system is killing Black men prematurely.”

Still, we know crisis reshapes history. In fraught moments, visionaries have come forth with ideas and actions that build a better society for all.

“Donald Trump has failed,” Taylor says. “He’s chosen to be a Reagan in a crisis that requires an FDR. We need someone who can think big, like a Horace Mann did for education in America.”

With Joe Biden elected president, Taylor says, we may be able to implement the structural changes — in health care, in criminal justice, in education, in economics — that will create a more just society.

Taylor says he wants to be hopeful, but history has shown that, at least in the Black community, progress comes with backlash. “The door opens, and it always closes back.”

If citizens and leaders don’t stand up for real, meaningful change now, the future actually won’t look too different — at least for Black America, he says.

“Fifty years from now, you’re going to be like, ‘Wait a minute. We’re still dealing with this?’”