Putting Down Roots

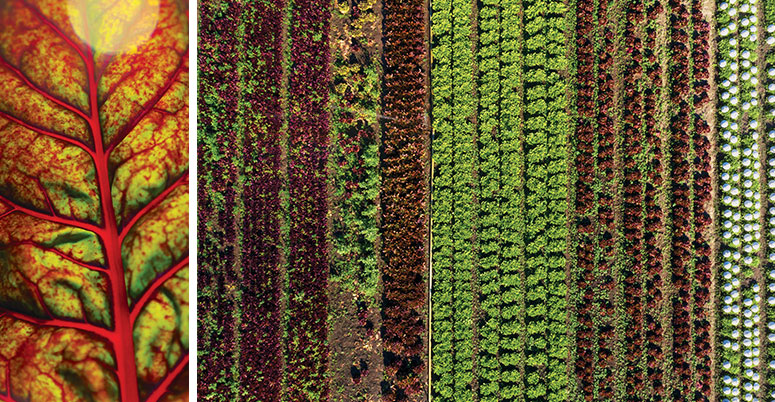

In the summer of 2017, when USF announced it bought a farm in Bolinas, California, you could hear rumbling all over campus. A farm. Really? In this time of tight budgets? In that town on the Marin County coast where locals remove the road signs so outsiders can’t find the place?

USF wasn’t looking to purchase a farm, USF President Paul J. Fitzgerald, S.J., said at the time. “What do we do with a farm?” he said. But USF went ahead and bought Star Route Farms, the state’s oldest certified organic farm. Thing is, the purchase wasn’t all that crazy, says Provost Don Heller. And today, two years later, the university’s investment has begun to bear fruit.

Paying Its Way

The $10.4 million purchase of Star Route Farms is being funded entirely by donors, Heller says. “It doesn’t have an impact on the university’s operating budget.” And in fact, as a working farm that supplies produce to 85 Bay Area restaurants and two farmers markets, at the Ferry Building and in Marin, the farm covers all of its costs. Any extra is used to keep up on improvements, including fixing up housing for the 20 farm workers who live there. As part of the purchase, USF also has a five-year commitment to lease farmland in Thermal, California, in the Coachella Valley, which enables Star Route Farms to grow produce and supply its customers year-round. The sale of produce covers the rent for the Thermal land, Heller says.

Aside from paying its own way, the farm has generated new philanthropic interest at USF. The university has received a bequest from an alumnus to create an endowment providing financial support for research, teaching, or service activities involving Star Route Farms. The endowment will provide about $40,000 annually to support projects that involve the use of the farm.

Serving the Jesuit Mission — and Students

Pope Francis, who is Jesuit, wrote this in his encyclical called Laudato Si’, or Care for Our Common Home:

Each community can take from the bounty of the earth whatever it needs for subsistence, but it also has the duty to protect the earth and to ensure its fruitfulness for coming generations.

If the university is to care for the earth, it helps to have some earth to care for — in a direct, hands-on way. “For me, as a plant-interested ecologist, the farm is an amazing resource, particularly for such an urban campus,” says Naupaka Zimmerman, assistant professor of biology. “It’s important for all of our students to learn that sustainable agriculture is absolutely critical to the survival of humanity. Period.”

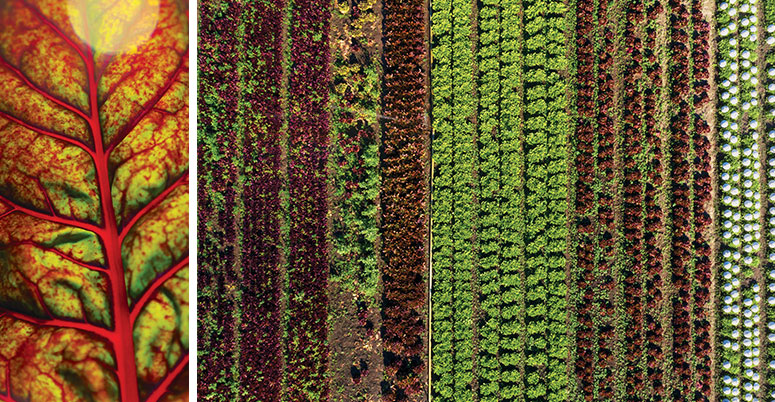

With 40 acres under cultivation and 60 acres of woods and ponds and wild hillside, Star Route Farms offers many educational opportunities — student field trips, research projects, and group workshops and retreats for students, staff, and faculty. The environmental science department wants to measure carbon storage in the soil to see if the farm is shrinking the university’s carbon footprint, and students have monitored water quality in the creek that flows through the farm.

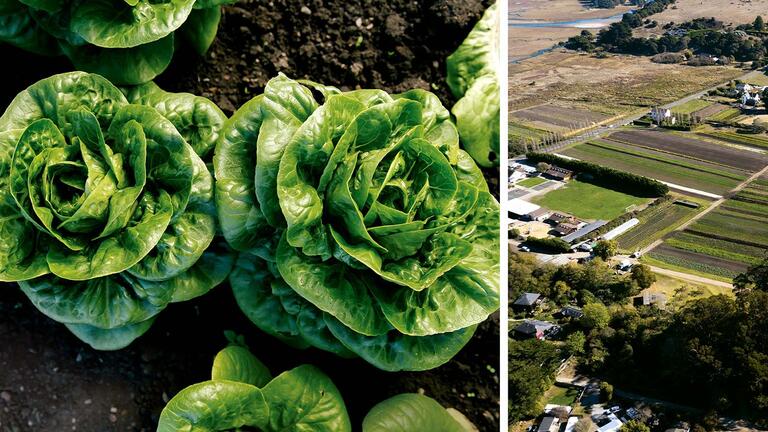

The hospitality management program is using Star Route Farms produce — everything from kale, tatsoi, and Little Gem lettuce to strawberries, blueberries, carrots, and artichokes — in cooking classes and for some university events. Students in a beverage management class are coming up with their own cocktails, using herbs and spices from the farm.

Biology students have visited the farm to study how drought affects pollination, and the undergraduate California Ecology class visits to study sustainable agriculture and ecosystem ecology — how living beings interact with their environment, says Zimmerman. And the first student research project is underway. Derek Newberger MS ’20, a biology student, collects leaf microorganisms from the cover crops at the farm, planted to collect nitrogen in the fields on which no chemicals are used. He is studying whether the microorganisms benefit the soil.

“I’m interested in agriculture and sustainability, and this is a spectacular opportunity to work with a working organic farm,” Newberger says. “If one cares about life, then the way we preserve farmland should reduce the burden of humans on our natural resources.”

Feeding the Whole Person

Star Route is also a popular retreat destination. The School of Nursing and Health Professions, University Ministry, and the hospitality management and philosophy departments, among others, have visited the farm for a day to recharge and reflect. The graduate creative writing program is considering a writers’ retreat.

“Star Route Farms and the beauty of Bolinas is a perfect combination for us to get this central insight of Pope Francis and see how we are all part of nature. And, that all of creation is connected,” says Donal Godfrey, S.J., associate director of faculty and staff spirituality.

Star Route Farms is not just a place for retreats, however. It is a working farm, and it takes a team of people — a manager, farm workers, delivery drivers — to keep it running.

Annabelle Lenderink, the farm's manager, was born on Curaçao, educated in Holland, and went to college in New Orleans. She moved to California to study organic farming in the early 1990s.

She walks across the farm, picking up flecks of trash that may have blown over from the road. She stops to check the lettuce — “it takes 65 to 75 days to grow a full head of romaine, you know” — or to fix the sprinkler near the Meyer lemon grove. At the roadside farm stand, she munches a carrot while saying hello to customers. She knows them by name.

“I came to the farm back in 1998, and I learned from the ground up,” she says.

Plants want to grow. You just have to get out of their way.

Lenderink invites university groups to visit the farm. She stops her work to give tours or explain how the water from the ponds is used to irrigate the crops in late summer. When asked what the first change at the farm was since USF took ownership, she smiles. “The growing fields have been fenced in with eight-foot fences to keep the deer out,” she says. “They ate three crops of romaine before we got the fence up.”

What Does the Future Hold?

In a state and a country where huge factory farms still bathe their crops in chemicals, Star Route Farms offers a glimpse of the future: small-scale food production that is proven to sustain the earth instead of damage it.

“Organic food is more popular than ever,” says Lenderink. “People realize it’s possible.”

Now that USF has bought the farm and has settled in, somewhat, to its role of landowner, it’s time to discover what this acreage by the sea holds in store for the university community.

“I think the connection to USF sets up the likelihood that more students from USF will go out there and actually be on a working farm,” says Zimmerman, the biology professor. “A lot of students are not aware of the way food is produced and what goes into growing crops and what they look like and feel like and smell like. This is part of USF now. This enables new opportunities to connect our students to sustainability.”