Colossal Discovery

It was the trip of a lifetime for Gretchen Coffman. Literally.

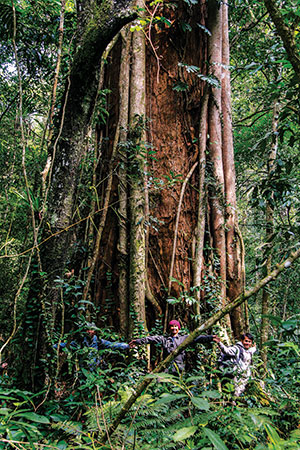

She was trekking on the Nakai Plateau in Laos, when she fell over a tree root. As she climbed back to her feet, Coffman realized she’d stumbled on an exposed root of a huge cypress tree. Not just any cypress tree. A Chinese swamp cypress, thought to be nearly extinct in the wild — and a close relative of the majestic California redwood. As she scanned the forest, she realized that beyond the one, there were dozens more.

"They were 20, 30, maybe 40 meters tall,” said Coffman, a USF assistant professor of environmental management. “Until I found those, there were only about 250 swamp cypress thought to survive in the wild in Vietnam, where they’ve stopped reproducing because of constant encroachment by coffee plantations and other agricultural development.”

Now, the restoration ecologist is leading an international effort to save the species with support from National Geographic and Philip Thomas, a renowned scientist for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the organization that maintains the endangered species list.

I thought we were losing the last seed-producing swamp cypress in the world — and I’d just discovered them."

“This species typifies the impact that humans have had on the natural environment over a comparatively short period of time, which alone makes it worth studying,” said Thomas, who’s also a scientist for the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. “It outlived the dinosaurs, survived meteorites and the shifting and changing of the continents and climates — there’s something incredibly robust and resilient about this tree. It’s only in the last 10,000 years, especially the last 1,000 years — with the explosion in the human population and the development of agriculture, particularly rice cultivation — that it seems to have finally met its match.”

The swamp cypress was once widespread in temperate areas throughout Asia. But in 2006, the trees were listed as critically endangered — one step from extinct in the wild. Coffman was the first scientist to discover the cypress stand on the plateau near the Nakai-Nam Theun National Protected Area (NPA) in 2007, while she was helping to develop a mitigation plan for the many species that would be impacted by the nearby construction of the largest hydropower dam in the country’s history.

Near-extinct tree sent to watery grave

By that time the dam, called Nam Theun 2, was already halfway built and funded by the World Bank. It also had wide public support because it promised millions of families in Laos and Thailand electricity for the first time. “I knew there was no stopping it,” Coffman said of the dam. “My heart sank when I realized that the incredibly rare trees I’d just found would be drowned.”

Several hundred, Coffman estimated, ended up under water — in spite of her objections.

“I had mixed feelings,” Coffman said. “I understood the dam would benefit the locals, that was a good thing. At the same time, I thought we were losing the last seed-producing swamp cypress in the world — and I’d just discovered them.”

Coffman couldn’t have known at the time, but the project became a model for dam construction in all Southeast Asia — one that scientists point to even today.

Before Nam Theun 2, it was unheard of in the region for scientists to be invited to study an area that was about to be dammed, Coffman said. Even more important, the Laotian government met extensively with 17 villages that had to be relocated and came to a mutual agreement, an unprecedented move. Each family received a newly built house with electricity, a new boat, and free job training, and their children benefited from new schools. The government also agreed to the 2007 environment mitigation plan Coffman helped develop, which included restoring some of the species drowned by the dam, the Chinese cypress among them, and paying for rangers to protect the 1,330-square-mile Nakai-Nam Theun NPA — the preserve located upstream from the cypress she first found on the plateau.

In spite of losing the cypress, Coffman refused to give up. She was convinced there were more swamp cypress in Laos, and she set out to find them before they disappeared forever.

In January 2015, Coffman returned to Nakai-Nam Theun NPA with an international contingent of scientists as well as funding and in-kind support from National Geographic, IUCN, the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, and USF. She’d received a tip on where more cypress grew and planned to find, measure, sample, and map as many as possible during a three-week winter break from classes.

The Chinese swamp cypress, once the backbone of forests in the region, support a wide range of flora and fauna, according to Coffman. Orchids and other epiphytes grow on the tree, and bees build hives high in its foliage. Ginger and rattan and other plants grow in the rich, spongy soil beneath, and a multitude of birds as well as black bears, sun bears, and wild boars make their homes in its shadow. Perhaps most important, forests like the one Coffman found are powerful agents for removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere — a vital trait in an era of climate change.

But human agriculture and construction led to the trees’ demise over centuries. Farmers felled them to plant rice, and the trees’ resistance to rot and infestation made them prized by builders.

It took four days’ travel from San Francisco to reach Nakai-Nam Theun NPA, an untamed environment infested with leeches and mosquitos. The team had to be on alert for roaming elephants, Bengal tigers, and poisonous snakes. Worse, there were unexploded bombs throughout the NPA, which was part of the Ho Chi Minh Trail during the Vietnam War.

Trek to a spiritual forest

To make it that far, Coffman had jumped through months of hoops to secure seven federal, regional, and local permissions — with each agency adding observers to the expedition. Her original team of seven grew to 30. The most unnerving additions were forest rangers with machine guns, reportedly to protect the growing team. Finally, Coffman was ready for the three-hour hike into an old-growth forest from a nearby village. Or so she thought. It turned out she still needed to convince the chiefs of three villages that bordered the forest that her team was there for science — not exploitation.

“White people come through their villages maybe once a year, so they don’t know or trust us. We had to promise not to divulge the trees’ locations,” Coffman said. “They were worried we would publicize it to outsiders and endanger their forest, which has spiritual and cultural significance.”

The chiefs had good reason for concern, Coffman learned. Local residents and government officials told stories of poachers sent from Vietnam by wealthy businessmen to cut down the cypress, hack them up into meter-long planks, and carry them on their backs to Vietnam, where intricate hardwood furniture was fashioned from them.

After days of negotiating with the chiefs, the way was cleared for the trek into the old-growth forest. The team had just over 24 hours to document the swamp cypress’ native environment — critical information that Coffman needed for a restoration plan. “I didn’t know if we’d get another chance to go back,” Coffman said. “I feared that if we didn’t get everything we needed, we’d have lost a great opportunity. But we found the trees. We found them, and I was so excited.”

Coffman wanted to know as much as possible about the old-growth trees’ environment — an environment untouched by humans — so that her team could locate a suitable habitat to plant young saplings.

In July 2015, Coffman and her team returned. They’ve found nearly 600 trees, to date. Her team carefully measured the trees’ heights and circumferences, took core samples to determine age, collected seeds, and mapped each tree using GPS so that subsequent measurements can be matched to track each tree’s development. So far, the oldest trees date back almost 300 years. But Coffman believes that some could be more than 1,000 years old.

A life-changing expedition

“I never imagined being part of such a discovery while I was in school,” said Robin Hunter MSEM ’15, Coffman’s environmental management research assistant during the January 2015 expedition. She mapped each tree with a GPS unit and created habitat models that included 37 different environmental variables such as rainfall, temperature, and elevation — to identify conditions in which the tree is likely to live.

“What I learned at USF, and working with Gretchen, gave me the chance to do what I love — work to preserve and restore our natural environment,” said Hunter, who’s putting her degree to work at Oakland-based Horizon Water and Environment, identifying plants, conducting fieldwork, and making maps as a watershed management scientist.

Shelley Bennett MSEM ’16, also a graduate student in environmental management, took over from Hunter as Coffman’s assistant and joined the July 2015 expedition. “Travelling to Laos was an incredible and life-changing experience,” she said. “I learned an immense amount about the effort that goes into planning a field expedition, especially arranging a project in a foreign country and working with many different government agencies and groups of people.”

Coffman’s focus on education isn’t reserved for her own students. She invited Vichith Lamxay, a professor of botany at the National University of Laos, to join the second expedition. Lamxay brought two botany students who joined the research effort, taking soil moisture measurements and collecting soil color and texture samples.

“I’m a field researcher by nature, but I love to teach,” Coffman said. “Training the next generation of scientists in these techniques is essential to the swamp cypress’ survival and recovery.” Her goal is to propagate the trees and rebuild their population in Laos, Vietnam, and other countries where they’ve been decimated. It’s a huge undertaking — which is why so much of her energy goes into connecting with local residents and international scientists.

“I can’t do this alone,” Coffman said. “So many others have the passion and skills to help, so why not invite them to join the team?”

Thirteen ecosystems are just a start

Coffman talks about the Chinese swamp cypress in all of her classes, not just her graduate courses. It’s a great way to excite and inspire students, she’s found. “There’s a sense of adventure,” she said. “It engages students. They see their teacher as an active scientist, field researcher, and conservationist.”

Luckily, not all of Coffman’s students have to trek to Laos to benefit from her expertise. At USF, her undergraduate students examine 13 Northern California ecosystems, then study one in depth. They create abstracts and present papers at an ecological conference at the end of the semester. And every other Saturday, her graduate students visit such places as the Bay Area’s most pristine salt marsh at China Camp State Park near San Rafael; one of the largest remaining old-growth redwood forests in the world at Big Basin Redwoods State Park, north of Santa Cruz; and one of the most bountiful marine environments on Earth at Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, off the coast of San Francisco.

Coffman brings her discipline to the broader campus as well: In 2012, her students began restoring native dunes plants on the west side of Lone Mountain. “We study how the drought has affected these plants by creating a health index and measuring their growth,” she said.

In the end, it's about what we choose to value.

Like in her teaching, the most important outcome of the Chinese swamp cypress project is education and outreach. “The scientists and students who were with me in Laos learned so much about doing research internationally — from sampling techniques to the collection and organization of data, and how to write up their findings in reports,” she said. “As a scientist, you’re taught to be objective, to sample and document and understand the ecology of the system. But as a conservation ecologist, you also have to protect the species that you’re working with. And that means working with people.”

Working with a Laos nursery, Coffman’s team successfully germinated 12 cypress trees from seeds over the past year — a scientific first. “It’s not easy, because we know very little about the species,” Coffman said. “For example, we just learned that their seeds are viable for just two weeks in November. Because swamp cypress are wind-pollinated, if it’s not windy enough or if it’s too rainy during that small window of time, then no seeds are pollinated that year.”

Acting before it’s too late

Of the 12 seedlings, four have grown into saplings about 8 feet tall. That’s far short of the 100 trees the Laotian government agreed to restore in Nakai-Nam Theun NPA, as part of the mitigation plan Coffman helped develop in 2007 — before the valley’s flooding.

“That’s what we’re working on,” Coffman said. “Now that we’ve found healthy, regenerative trees, the next step is to work with the government watershed management agency and local villages to develop a long-term plan to repopulate the Chinese swamp cypress in this area.”

Coffman’s team is working with villagers, forest rangers, and watershed management officials to build a support network. They’ve taught elementary school children about the trees, made dozens of presentations to energy and environmental experts in Laos, and appeared at conferences — not to mention invited scientists, university professors and students, local forest rangers, and tribal leaders to join their work.

The idea is for the local residents to eventually take over the stewardship of the swamp cypress restoration and build partnerships to protect the trees from logging and poaching — as well as to plant new cypress, Coffman said.

“Humans have a propensity for waiting until a species is on the brink of extinction before they decide it’s important enough to protect,” Coffman said. “Look at the iconic old-growth redwood forests in California, the elephants in Africa, wolves in Yellowstone National Park, and the giant panda in China. The Chinese swamp cypress is no exception.”

“We know so little about this species. But what we do know is that the forested wetland ecosystems it grows in are critical to our planet’s health — they removed carbon pollution from the air at exceptionally high rates, filter water better than any system humans have built, and provide essential habitat for a whole host of other wildlife that contribute to the environment’s well-being,” she said.

For Coffman, finding the swamp cypress was just a start. Saving and restoring the trees to their rightful place in the ecosystem is what’s meaningful.

“In the end, it’s about what we choose to value," Coffman said.