Cleaning Up San Francisco Bay's Mercury Contamination

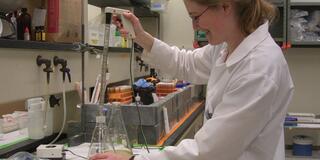

Allison Luengen, University of San Francisco assistant professor of environmental sciences, is at the center of research to discover exactly how mercury makes its way into San Francisco Bay and thereby the food chain of Bay Area residents’ and develop possible mitigation measures for the contamination.

Visit any pier frequented by fishermen on the San Francisco Bay or drop by San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf and you’ll see signs warning of the health risks associated with eating fish caught in the bay.

Tens of millions of pounds of mercury mined along the California coast during the mid-to-late 1800s and early 1900s and used to amalgamate with gold at slurry mines in the Sierra Nevada washed into Sierra and delta waterways during the Gold Rush era, settling into soil and sediment and making its way into San Francisco Bay.

Now it is in the food chain, contaminating bay fish such as striped bass, sturgeon, and shark to such an extent that women of childbearing age or pregnant or nursing women and children are advised to eat no more than one meal of those fish a month. Women beyond childbearing age and men should eat only two meals of those fish a month, according to the California Office of Environmental Health and Hazard Assessment.

“Unlike hazardous materials sites that are geographically contained and can be cleaned up using traditional methods, California’s mercury contamination has seeped into streams and rivers for decades and become so diffused from the mountains to the bay that it’s really hard to clean up,” Luengen said.

Her research shows that mercury, in the form of methylmercury, is absorbed by waterborne phytoplankton, tiny plant-like organisms at the base of the food chain, which are then consumed by larval fish and so on up the food chain.

By studying a number of tributaries to the San Francisco Bay, Luengen, and fellow researchers Nicholas Fisher of Stony Brook University and Brian Bergamaschi of the USGS Water Science Center, have zeroed in on water chemistry and its ability to inhibit methylmercury from getting into the phytoplankton and fish.

Understanding how chloride, water pH, and dissolved organic matter (DOM) interact to affect the intake of methylmercury by phytoplankton could offer solutions or strategies for preventing mercury from working its way up the food chain, Luengen said.

The group’s most promising findings to date – presented at the Goldschmidt: Earth, Energy, and the Environment conference in Knoxville, Ten. in June – are that the presence of DOM, whether it’s decaying aquatic plant life or storm drain runoff, decreases the accumulation of methylmercury in phytoplankton. That doesn’t mean that dumping organic material in San Francisco Bay tributaries is a silver bullet solution, however. More investigation is needed to understand how DOM impacts the conversion of mercury into methylmercury, as well as how it effects aquatic environments and their inhabitants as a whole, Luengen said.

That is the focus of the next project Luengen is working on with Fisher, along with Jonathan Cole, senior scientist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, for which the group recently received more than $200,000 in funding from New York State Energy Research and Development Authority. Their latest research begins this summer and will take place on the Hudson River Estuary.