The Museum Makers

Class assignment: Go to USF’s Rare Book Room. Select some of the oldest books in existence, by authors like Dante and Machiavelli, and 500-year-old prints by one of the greatest artists of the Northern Renaissance.

Create a compelling, museum-quality exhibit from scratch. Display it in a professional gallery and then invite the world.

Any questions?

“Some of them kind of creak when you open them, and they only open so wide because the leather is getting stiff,” says graduate student Hillary Eichinger ’15, from Portland, Ore., who was studying rare and historically important works from USF’s permanent collection. The oldest—a leaf from the Gutenberg Bible—was printed around 1455.

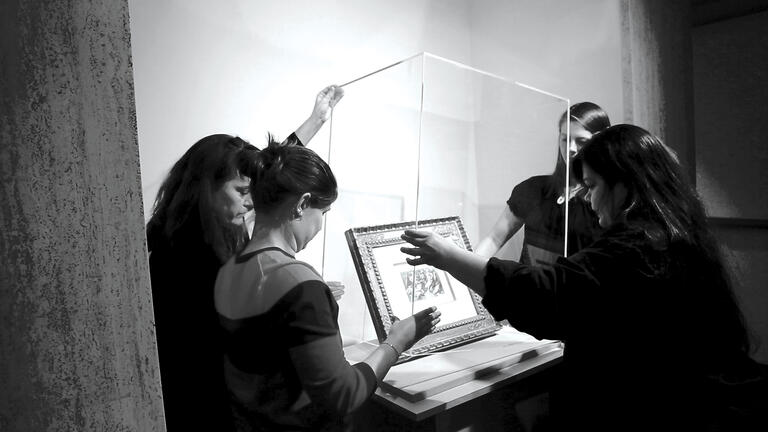

John Hawk, head librarian, Special Collections & University Archives, was keeping a watchful eye on Eichinger and her classmates as they worked. Hawk is in charge of USF’s Donohue Rare Book Room, located on the third floor of Gleeson Library.

His rules were simple but crucial: A rare book will open only as much as it wants to; don’t force it. Turn pages slowly and deliberately, so they don’t tear. Watch your fingernails: They scratch the fragile spines. No watches. No rings. Stay focused.

And no gloves. “The trend has moved away from using gloves in reading rooms. Unless you really know how to work with them, it’s easy to tear paper and damage books,” Hawk says. “The essential thing is to have clean hands.”

There was little need to remind the students that these extraordinary books demanded extraordinary care.

“We all understood the importance of these works because we had been researching them,” says Kathryn Booth ’15, a San Diego native. “That made them even more special, and we treated them with a different kind of care, because we knew their stories. They became really important objects to us personally.”

The Ultimate Class Project

a student-curated exhibit at Thacher Gallery.

Fourteen graduate students were about to begin the only assignment for their Curatorial Studies Practicum: They would build a professional-quality art exhibition, top to bottom, and then invite the public.

“The idea was to introduce graduate students to working directly with objects from the university’s collection, historically interesting and difficult objects, and to challenge them to put them together in a way that would be exciting and interesting and relevant to today’s world,” says Catherine Lusheck, assistant professor of art history/arts management, who teaches the practicum.

Lusheck and Hawk developed the idea and recruited Glori Simmons, director of USF’s Mary and Carter Thacher Gallery, where the core of the exhibition would be displayed.

It was win-win: Students would get extraordinary experience that might help them land a job or an internship, and USF could showcase important work from its permanent collection that had never been exhibited together.

The practicum is part of USF’s new graduate program in Museum Studies. The program prepares students for leadership positions in cultural institutions of all kinds and gives them big-picture knowledge of museum operations, everything from preservation to fundraising. They also embrace museums as agents for social change.

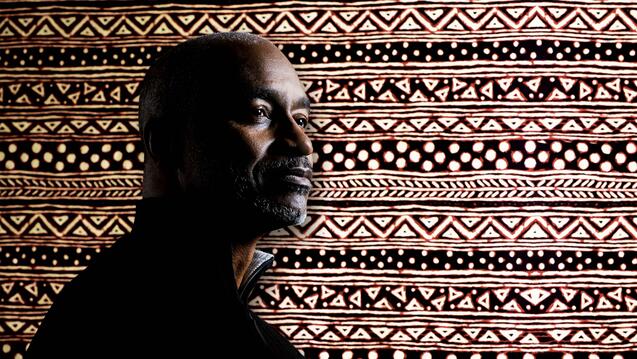

“Students who select our program are also passionate about social justice issues,” says Paula Birnbaum, the program’s director and associate professor of art history/arts management. “We regularly work with institutions on the representation of diversity and human rights issues, and our students realize the potential of museums to contribute to more equitable and just societies.”

The first students to complete the 16-month program graduated in December 2014, and they’re now working at places such as the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum, the Pacific Science Center in Seattle, and the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, NY.

“What I really liked about the program is that it encompassed all aspects of museum work, everything from museums to the law, copyright issues, museum financing, and managing the collections,” says New York native Merrill Amos ’14.

Our students realize the potential of museums to contribute to more equitable and just societies.”

She’s now the curator at the Women’s Hall of Fame. It is moving to a new home next year, four times bigger than the current one, and Amos is the decider. “I will be developing the exhibit and working with our architects on designing the exhibit space,” she says. “Also, I’ve taken on the role of collections manager, as well as writing the collections policy for the hall and making sure our artifacts are properly preserved.”

Students say the program excels in an especially crucial area: connecting them with high-level museum professionals and helping them build a solid professional network. “It’s a tough job market right now. There are a lot of qualified, passionate people who want these jobs,” Amos says. “I think this makes the professional contacts from our professors all the more valuable. As within any industry, it’s all about who you know.”

Pressing Matters

The materials the students were working with were produced during a pivotal time in history, when Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press was taking hold in Europe and the slow, costly, error-prone process of reproducing texts by hand was rendered obsolete.

Gutenberg’s machine was a marvel, making copies faster, cheaper, and better than anyone had imagined was possible. He introduced it around 1440 in Germany, and within 50 years, an estimated 10 million volumes had been printed across Europe.

The consequences of this disruptive technology were enormous. It introduced mass communication and was a catalyst for the scientific revolution. It also led to uprisings and threatened monarchies and even the survival of the Roman Catholic Church. Many historians believe it is the most significant event in modern history.

“The technology allowed for thinkers to get their new ideas out there,” explains Eichinger. “It was basically a mode of transportation for ideas, one that didn’t exist before in the West.”

What’s the Big Idea?

The “big idea” is central to any modern museum exhibit. It’s the key concept that defines the show, helps sharpen its focus, and unifies its many disparate parts, like a thesis sentence in a term paper.

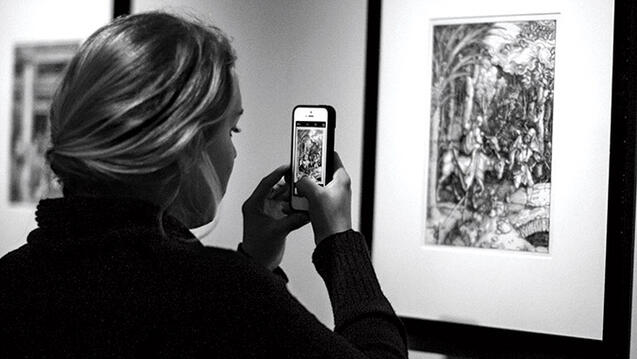

a print that is part of the university’s permanent collection.

Photo by Gino Luigi Mascardo ’16.

The students decided the big idea for their exhibit was this: Innovative technology holds the potential to foster creative and social change.

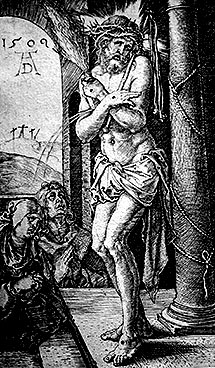

The exhibit’s focus would be remarkable woodcut and engraved prints by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), a German artist many consider the greatest of the Northern Renaissance. He was a painter, a writer, and a mathematician, but his prints were revolutionary, and they brought him international acclaim and influence in his 20s.

Until Dürer, woodcut prints featured bold lines and almost no detail. This type of printmaking is notoriously difficult because of the wood itself: It splinters and cracks, it swells and contracts, and the thinly carved lines used to give the images detail are often damaged during printing.

Dürer’s prints were so rich with detail they stunned anyone who saw them. They even had shading, which had seemed impossible to achieve. The virtuoso artist single-handedly elevated printing to an art form.

It’s unusual for a university to own so many Dürer prints, Lusheck says. USF owns three complete sets: the Life of the Virgin series (20 prints), the Engraved Passion series (16 prints), and the Small Passion series (36 prints). The students would feature all 72 prints in their show.

The prints were a gift to the university from businessman Reinhard F. Timken-Zinkann in 1957, along with many of the books in the exhibit. He collected them in his German homeland, but he left Germany at the start of WWII and settled in Palo Alto, Calif.

“I would imagine any major museum or university collection at home or abroad would be impressed by this collection,” Lusheck says.

Details, Details

“This wasn’t a hypothetical project, it was an actual show,” Booth says. There was a hard-and-fast deadline.

And the to-do list seemed endless: Research the artists and their work, create banners and posters, write talking points and develop a media plan, produce a self-guided tour, post on social media, author a website, on and on.

“A lot of things go into these exhibitions, a lot of really small things that you can’t learn in a book,” Eichinger says.

The class broke into groups in three major categories: subject matter, design, and public relations. Eichinger was one of two project managers assigned to guide and update the groups and make sure everything came together and supported the Big Idea.

She was also a member of the design group. “We did a lot of the layout, setting the mood and the tone, the look of the labels, and the color choices and font choices,” she says.

Students also had to consider the show’s physicality: where the display cases were placed, the objects in those cases, the flow of the room, and how real-life gallerygoers would interact with the exhibit.

“It was really, really hard,” Booth says.“It was more work than I thought it was going to be, more late nights. And just learning to work with every kind of personality—which is a life lesson to have forever.”

Albrecht Dürer, “Christ Taken Captive” (detail),

from The Small Passion woodcut series, 1511.

Donohue Rare Book Room, Gleeson Library,

University of San Francisco.

The Hardest Part

The students may have mastered Twitter and its 140-character limit, but they struggled with the 50-word limit on the exhibit’s description labels.

Every object needed one. The goal was to capture its essence, or distill its most interesting facts, using language that wasn’t too academic or dumbed-down.“Labels can really make or break an exhibit,” Booth says. “It’s a huge amount of information to synthesize. That was a really big struggle, and writing those labels in a way that would be interesting and fun for our audience.”

Why only 50 words?

Museum fatigue. “There’s only so much people are going to read,” Booth says. “And if they can’t understand something, they walk away. I’ve seen it happen a million times.”

Dürer Debut

It was Jan. 26, 2015, opening day for Reformations: Dürer & the New Age of Print.

Visitors entered a dimly lit gallery, and it took a few seconds for their eyes to adjust. But this wasn’t mood lighting, it was insurance. The prints and books are fragile, and light is the enemy. The show would run only three weeks to protect the objects.

The exhibit started in the Thacher Gallery and continued in the Rare Book Room upstairs. There were 117 works on display, including more than 40 books, by authors like Dante, Machiavelli, Desiderius Erasmus, Thomas More, Luca Pacioli, and Virgil.

Book highlights included Vitruvius’s On Architecture (1511); a rare Book of Hours (1497), a Christian devotional book popular during the Middle Ages; Thomas More’s seminal Utopia, dated 1518; and a complete copy of the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493), a lavishly illustrated biblical history of the world.

Students provided magnifying glasses so patrons could appreciate the rich detail of the Dürer prints.

“I was so proud to be a part of it,” Hawk says. “It was one of the most professional exhibitions I have had a privilege to be a part of. From conceptualizing the exhibit to the labels, everything was done really well.”

Albrecht Dürer, “Man of Sorrows,”

from The Small Engraved Passion series, 1509.

Donohue Rare Book Room, Gleeson Library,

University of San Francisco.

Experience Matters

Shortly after the exhibit, Booth was interviewing for an internship at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. As part of the program, students must complete an internship lasting at least 12 weeks.

“What was it like working with the Dürers?” they asked.

“These guys are around the most amazing art, from all over the world, every day,” she says, “but they seemed genuinely interested in my experience working on the exhibit and with the Dürer prints.”

She got the internship and hopes to turn it into a permanent job. She believes the project’s hands-on experience gave her the edge.

“Even in the struggles, there were 10 lessons I was able to take away,” Booth says. “Every single day brought a fresh hell, but I feel like I am more professional and I am better because of it.

“And when I saw the lights turned on, and I saw all the cases put out, and I saw all the books in place, it was a very emotional experience.”